Culture as a Field of Human Action (An Essay Concerning the Construction of Psychoculturalogical Theory)

Body:

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 4 (2016 9) 837-853

УДК 130.2 + 159.9.01

Svetlana V. Lourié*

Sociological Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences

25/14, 7th Krasnoyarmeyskaya Str., St. Petersburg, 190005, Russia

Received 07.01.2016, received in revised form 19.02.2016, accepted 14.03.2016

This article is about the hypothesis of a generalized cultural script that permeates all aspects of personal and social life. A generalized cultural script is culture-specific and is formed in the human consciousness during socialization and enculturation. It happens when special cultural event scripts are condensed and generalized in the person’s consciousness. The article studies a cultural context for the functioning of a generalized cultural script, or a sociocultural system consisting of different types of artefacts and presenting, generally, a system of intentions. The generalized cultural script itself is seen as an intentional artefact system that transforms a human into an intentional personality. It sets the problem of the relation between intentionality of the human world and freedom of will.

Keywords: generalized cultural script, sociocultural system, cultural constants, intentional world, intentional personality, set, artefact, cognition, enculturation, freedom of will. DOI: 10.17516/1997-

1370-2016-9-4-837-853.

Research area: sociology, culture studies.

© Siberian Federal University. All rights reserved *

Corresponding author E-mail address: svlourie@gmail.com

The question on the interconnection between culture and psychology seems trivial, as the interconnection is evident. However, in reality it is not so simple. For many decades anthropologists have been suggesting different versions attempting to explain the interconnection between culture and psychology, but all of them were disposed of one by one. The idea that a human personality is formed in the early years of life in the process of socialization determined by culture seemed self-evident, but as no one could prove it, it was also disposed after all. All scientific descriptions of national character were based upon this particular idea, that claimed to be theoretically substantiated, relied on. Back in psychological anthropology there were several concepts of intracultural integrators that reduced personality and culture to common denominator by pointing out such dominating personal peculiarities of a culture’s members, as “basic personality structure”, “modal personality” and others. However, by the mid-20th century it had been recognized that no culture, not even any of those called primitive, had anything similar to “modal personality structure” (Inkeles, Levinson 1969: 427-428).

For a long while after that the connection between culture and psychology was considered nonexistent or, in any case, to be ignored or possible to factor out without prejudice to science, as it was believed that psychology did not make a direct impact on the functioning of culture, just like culture made no direct impact on the formation and functioning of human psyche, and all the so-called cultural-psychological processes were nothing but a phantom. Then it was suggested that anthropology, psychology, sociology, social psychology might exist independently from each other without penetrating into each other’s field, and in their mechanical aggregate they were capable of explaining all phenomena of cultural, and social life, as well as formation and development of human personality. However, at the time there was no field of research left for psychological anthropology.

As long as anthropology studies the functioning of culture, the question was finally reduced to the definition of culture. Since the early 60-s and until the early 80-s the majority of anthropologists saw culture as a system of meanings (signs, symbols) that presented a sophisticated and tight entwinement (due to its out-scientific character, post-modernist critical approach in cultural anthropology was not taken into account). The culture bearers, their words, dialogues, actions and interactions were also seen as meanings (signs, symbols). Therefore, culture turned explainable in its own terms. As understood, before it had also been suggested that people thought somehow and reacted somehow to the outer world, but it had never been recognized as a phenomenon directly connected to culture. It was common to believe that to understand a culture it was enough to know some explicit human actions, such as their visible deeds and utterances that were interpreted from the anthropological point of view. However, what the people thought, what they felt, what emotions they experienced and concealed, what they preferred to hide and why, what they assumed by this or that statement, what they realized and what remained unrealized, what the real motivation for human behavior might be, all these were considered to be the subject of psychology, which was of no interest for anthropologists. This approach (named “symbolic anthropology”) was evidently limited, though internally consistent. It was impossible to be easily upturned; it had to be overcome. That is the main question set to psychological anthropology is: how to prove the inextricable interdependence of culture and psychology.

Since the late 20th century, one of the peculiarities of psychological anthropology has been its adoption of the cognitive approach terminology. The cognitivist terminology apparatus was used to overcome the antipsychologism of the symbolic approach, at the same time preserving all the constructive elements present in the latter. in the discussion cognitive and symbolic anthropologies concerned, first of all, one of the most underlying questions: are there any cultural systems within or beyond the human mind? Cognitive anthropology studies human mind and suggests that culture is concentrated inside a person. Symbolic anthropology studies objectivized culture and has no interest for what is happening inside the mind: according to it, culture lies beyond the human psyche. At the same time psychological anthropologists strived to prove that the internal and external systems of meanings were interconnected, and, moreover, that this connection was able to produce motivational mindset of a person, thereby provoking human activity.

The present article suggests such model of culture that assumes a direct connection between culture and psychology; but we will study the question from a new angle, which, on one hand, complies with all the achievements of the modern psychological and cognitive anthropologies, and on the other, respects the achievements of Russian science. Let us attempt to trace the culturally and psychologically determined human behaviour from individual perception of the outer world to the functioning of society as a whole from this point of view.

***

Let us begin with the question of how external world realities turn into intrapsychical cultural realities, or, “meaning systems”, according to the terminology introduced by American cognitive anthropologist Roy D’Andrade. We shall also use the “material flow” term D’Andrade defined as follows: “There is a major class of human phenomena that is not organized as meaning systems, which I term material flow. By material flow I mean the movement of goods, services, messages, people, genes, diseases, and other potentially countable entities in space and time” (D’Andrade 1984:110). As we suppose (perhaps, operating the term somewhat wider than D’Andrade did himself), “material flow” may include any other phenomena that did not become artefacts for these or those reasons, and, therefore, are not fully perceived by people in the culture, as they are not meaningfully represented.

To be perceived by people, phenomena need to become artefacts or “meaning systems”: mental artefact complexes that are included into culture understood as a “field of action”. Very tentatively, we shall interpret the notion of culture on the basis of the definition formulated by German cultural psychologist Ernst Boesch. According to him, “Culture is a field of action, whose contents range from objects made and used by human beings to institutions, ideas and myths. Being an action field, culture offers possibilities of, but by the same token stipulates conditions for, action; it circumscribes goals, which can be reached by certain means, but establishes limits, too, the correct or deviant actions. The relationship between the different material as well as ideational contents of the cultural field of action is a systemic one; i.e., transformations in one part of the system can have an impact on any other part” (Boesch 1991: р. 29). In order to become a component of a “cultural field of action”, a “material flow” element has to go through some mental operations. In this process some components of the “material flow” will inevitably remain beyond the human perception as lying outside the “intentional world” of a human being.

Here is what cultural psychologist Richard Shweder writes of intentional worlds: “Intentional things are causally active, but only by virtue of our mental representations of them. Intentional things have no “natural” reality or identity separate from human understandings and activities. Intentional worlds do not exist independently of the intentional states (beliefs, desires, emotions) directed at them and by them, by the persons who live in them” (Shweder 1991: 48-49). Moreover, Shweder says: “Intentional worlds are human artefactual worlds populated with products of our own design. <…> A sociocultural environment is an intentional world. It is an intentional world because its existence is real, factual, and forceful, but only as long as there exists a community of persons whose beliefs, desires, emotions, purposes and other mental representations are directed at it, and are thereby influenced by it” (Shweder 1991: 74). Therefore Shweder, besides the “intentional world” notion, introduces the notion of an “intentional person”: “Intentional persons and intentional worlds are interdependent things that get dialectically constituted and reconstituted through the intentional activities and practices that are their products…” (Shweder 1991: 101).

***

So, how do external world realities become intrapsychic cultural realities?

A part of “material flow” elements go through it automatically in the process of transmission. Progressively, as a child socializes, he adopts certain “event cultural scripts”, and as he adopts these cultural scripts, he also digests its components, from separate artefacts and artefact complexes to cultural schemes or models of behaviour. In other words, a child perceives whole cultural schemes deployed in time. As children get involved into the “interpsychic” (interpersonal) interaction with other people, this interaction gradually becomes “intrapsychic” (internal, psychologically adopted) or “interiorized”, (Miller 1993: 421).

According to Katherine Nelson, socializing their children, adults do more about directing their actions and setting their goals than about teaching them directly, immediately. Adults use their cultural scripts’ knowledge to set some limits to thus, the children action, thereby allowing children get involved into the role behaviour they are expected to show, i.e. act in accordance with a definite cultural script. This way the adoption of such scripts plays the central role in culture adoption (Nelson 1981: 110). At the same time, the whole cultural context determines the selection and implementation of the adopted scripts. Adopting such cultural scripts, the child also adopts artefacts around him, appropriate models of interaction and ideational contents of the cultural field of action, and the “intentional world” itself where he is going to live (Cole 1996: 208). And the children themselves become cultural objects, artefacts, as they enter the world.

Another part of “material flow” elements is adopted by means of some constant perception complexes belonging to a certain culture (we shall talk about it later), that correct the process of human perception bringing it into a culture-determined framework. By means of these constant complexes, an object or a phenomenon gets represented in the human mind, i.e. becomes an artefact. Here we may, to some extent, agree with the statement by psychological anthropologist Theodore Schwartz that culture consists of derivatives of experience, more or less organized (Schwartz 1994: 324-325).

Let us summarize everything said above and formulate some key suggestions to be discussed further. First of all, we assume that constant perception complexes themselves can be regarded as artefacts. Being specific psychic processes that regulate the sociocultural activities of a person, they are also a product of cultural activities of people and, therefore, may be presented as culture-determined, and unconscious elements of human psyche. Secondly, if a person “learns” a certain way of perception through his participation in a culture, or, to be more precise, in various scripts it provides, perception and activity should be regarded as two tightly intertwined processes. Therefore, we may draw a preliminary conclusion and suggest that structure-forming elements of a culture are the perception paradigms that determine the character of human activity in the world. Thirdly, the paradigms that determine the structure and, partially, the contents of a culture itself, as a rule, remain non-realized, as otherwise a person would have been able to construct a culture and convenient cultural scripts at his own choice relatively easily. And, fourthly, these paradigms are immediately correlated with the artefacts of culture and sets of the person to them. Let us begin the analysis of the above statements from the latter, i.e. from the notions of artefacts and sets.

***

The notion of “artefacts” is quite diverse today. It leads to the natural tendency of building an artefact hierarchy. The most widely spread hierarchy is the one suggested by Marx Wartofsky which goes as follows: (1) primary artefacts: material and ideal artefacts (objects or phenomena, as well as our representations of them); (2) secondary artefacts: representations of models of actions with primary artefacts; and (3) tertiary artefacts: the “free game” (operation of artefacts with no relation to the external world, its tendencies or any associated necessities) (Wartofsky 1979). Using a similar scheme, Michael Cole adds “cognitive artefacts” into his hierarchy (Cole 2003). The concept of “cognitive artefact” was initially suggested by Donald Norman whose objective was to reveal how and when the cognition of physical artefacts is formed in the human mind (Norman 1975). For Norman, thinking is an autonomous kind of human activity, and artefacts are something external for human thinking. They influence, but do not construct it; they cannot be active inside human psyche. However, the most important point for Cole is that an artefact acts within the cognitive system, and cognition is a process that occurs in an individual’s head. According to Cole, cognitive artefacts set up some information processing mechanisms (Cole 2003). Cole’s expansion of the notion brings its advantages. It gives us an opportunity to define not only the objects and phenomena, external for a human mind as artefacts, but also classify the intrapsychical ones as artefacts if they have been developed as a result of some cultural processes. Cole speaks of the “creatures whose minds are made through artefacts” and claims that “articles are, in some respects, models. Their structures carry within them, so to speak, a “theory” of both the human who is using them and the range of environmental circumstances in which they will be normatively used <…> as a synthesized ensemble that satisfices the constraints of the human user and the task at hand”. Cole believes that “at the same time artefacts are transformers, enabling the metamorphoses of what we refer to as external into internal and vice versa” and supposes that “because they enter intimately into human goal directed action, there is a functional aspect to all artefact-mediated action. And for the same reasons artefacts embody values (oughts, shoulds, and musts); in this sense all culturally mediated action is, at least implicitly, moral action” (Cole 2003). Cole does not speak directly of the motivational components of artefacts, but for him artefacts are, on one hand, procedural constructs, and on the other, value constructs, and therefore, as such, they cannot but perform the motivation function.

Concerning the latter aspect, a researcher similar to Cole is Herbert Simon, for whom artefacts always remain a product of human activity, i.e. they are “synthesized by human beings” (Simon 1981: 8). Moreover, it is relevant for us that Simon also speaks of such components of artefacts as goals, (as the motivation component of artefacts cannot just be left out in everything that concerns goals), functions (the process component is evident) and acts of adaptations (including the psychological ones connected with the “intentional worlds”).

The resulting hierarchy of values is the following: (1) material artefacts (2) ideal artefacts (let us define them as miscellaneous, as all of them are not the same) (3) cognitive artefacts, representations or schemes of an object in the consciousness or sub-consciousness of a person, (4) models of actions with artefacts (including scripts), as well as (5) goals (after Simon) and values (after Cole), adding (6) intentional worlds (after Shweder) that are also artefacts that can be compared to tertiary artefacts of M. Wartofsky. After D’Andrade, (1) are related to the category of symbols (D’Andrade 1994), (2) – to meaning systems, (3), (4), and (5) – to schemes of various types.

So, we can see that cognitive anthropologists and cultural psychologists speak of artefacts as of mental phenomena. We shall follow them, but we shall try to deepen this approach. To do this, let us turn to the concept of a “set” just as we promised before.

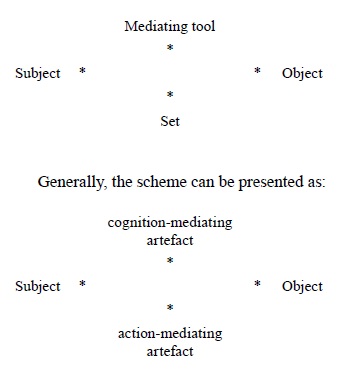

American cultural psychologists are mostly thrilled about the artefact theory by Soviet psychologist L.S. Vygotsky and particularly about his famous triangle of “subject – mediating tool – object” (Cole, 1996). Even though, according to Vygotsky, artefacts do not lie in such evidently mental sphere as they are in the vision of American cultural psychologists, in Soviet science Vygotsky’s theory had a sort of its mirror and mental reflection in the works by D.N. Uznadze, less known internationally. He suggested his own triangle of a “stimulus – set (unconscious readiness, willingness) for action – reaction”, which can be easily transformed into “subject – set – object”. Remaining within cultural psychology tradition to classify mental complexes as artefacts, we see that the “set” mentioned by Uznadze may be also qualified as an artefact. Comparing the triangles of Vygotsky and Uznadze (no one is known to have done it before), we get the following result:

Generally, the scheme can be presented as: According to Uznadze, a set determines “a subject as a whole, which enters into a relation with the reality, therefore getting forced to turn to some psychic processes for help. Indeed, the subject itself in this case is primary, while its activity is something derivate” (Uznadze 1961: 39-40, 169). And as according to Uznadze, a set is subconscious and is a modus of a whole personality, connected to a category of activity expressed through the readiness for some action, it is possible, with a proviso, also speak of an acting human personality as of an artefact.

The last statement matches cultural psychology perfectly; one of its representatives, Richard Shweder, introduced the concept of “intentional personalities” equally with the concept of “intentional worlds”. If “intentional worlds” (our sociocultural medium is also one of them), after Shweder, are artefact worlds, then “intentional personalities”, correspondingly, are artefact personalities, or, in other words, personalities producing material and ideal artefacts, running the cognition process through cognitive artefacts and performing actions with the sets of their personalities, withdrawing new “meaning systems” from the “material flow”. Cognitive artefacts, “meaning systems” and sets as artefacts are tightly intertwined. As stated by Uznadze’s follower, Sh.A. Nadirashvili, with the occurrence of a set to act in a certain direction, a person “influenced by it, notices and considers only those objects and phenomena that are connected to the set in this or that way. Neutral objects and phenomena, irrelevant for such set, remain unnoticed. The statement has been proven by a number of experimental results… Only those thoughts and contents of consciousness pop up in the person’s memory, that are related to the current set in this or that way. Matching this to the concept of “meaning systems” and “material flow” by Roy D’Andrade, we see that we speak of the same thing. But essentially Nadirashvili also speaks of the way how “flow material” elements become “meaning systems” through the mediation of perception complexes born by sets. The function of a set is to select objects, contents of consciousness, general experience and knowledge from the surrounding medium and the person’s previous experience that are necessary for the desired behaviour” (Nadirashvili 1978: 12). It means that it is only action that is determined by the a; at the same time, it is also perception, and interpretation. Action and perception act as an inseparable integrity, determined by one common set, which, in its turn, is determined by what Uznadze referred to as “modus of personality”.

Therefore, being an artefact which can be regarded both as (3 – cognitive artefact) and as (4 – model of action) within the hierarchy shown above, a set is related to the integrated cultural field (to 6 –“intentional world” and “intentional personality). A set is mediated by the connection between personality and cultural field. And as, according to Uznadze, a set may be fixed, i.e. stable, continuous, we may also say that a determining culture, a set underlies various cultural representations.

So, subconscious sets (consciousness is not involved at all!) “filter” the “material flow”, promoting something into “meaning systems”, and returning some former “meaning systems” into “material flow”. This way they determine the perception of both external world and our inner experience. Therefore, sets work as tools for representing an artefact and our consciousness as an artefact in the process of action, and determining the direction of such action.

As we are speaking of processes that occur within the framework of culture, we may mention not only exclusively psychological, but also some cultural and psychological complexes involved in the representation process, uniting in themselves the “meaning systems”, models of actions and sets, that in totality constitute cognitive artefacts (or perception complexes).

***

In the context of everything said above let us look at cognitive artefacts as at perception complexes. Being specific psychic processes, regulated (besides conscious regulation, it can be done unconsciously, through sets) by sociocultural activity of a person (consisting of cultural models of action, a part of which are unconscious, i.e. based on the existing sets), perception complexes themselves are a product of cultural activity of a person. Moreover, in cognitive artefacts even the procedural components of perception themselves (not only their result) implicitly contain and assume the presence of certain action models. Indeed, in a way they can be taken as a special case of cognitive artefacts, but it is relevant for us to outline the perceptive-activitive artefacts. It means that we may speak of the perceptive-activitive artefacts that integrate models of action with models of perception. This is what we call “cultural constants”, one of the key terms of our own concept of culture we are now approaching.

But let us return to “meaning systems”. They may both appear in the process of activity by themselves (extracted from “material flow”), and provoke such activity (actualizing the cognition connected to the “meaning system”). It does not only happen through its motivation function that joins culture with psychology, as mentioned by D’Andrade (D’Andrade 1994) and some other psychological anthropologists, such as Milford Spiro (Spiro 1984) or Robert LeVine (LeVine 1984), but also through a set, an underlying intention of human personality, developed (at least partially) and acting within a cultural framework, i.e. through transforming motivation into an instinctive necessity to do something in a certain way (with an appropriate cultural pattern). As claimed by Nadirashvili, this necessity may be fixed: “Such attitude to things can be situational, momentary, but it may get fixed and become chronic… In the process of set fixing some laws have been found that aid the formation of a certain personality type” (Nadirashvili 1978: 13). An inclination to “synthesizing” these or those “meaning systems” becomes fixed. A way of perceiving reality in the way determined by one’s culture also becomes fixed. So does motivation for some certain activity. Such fixed cognitive-perceptivemotivation-pattern complexes are what we call “cultural constants”, where we easily find the interconnection between cognitive artefacts and set-artefacts that have been developed in the process of human activity, and, particularly, in the process of interaction between individuals actualizing various cultural scripts.

***

A complex of cultural constants is a schematic prism through which a person looks at the world where he must act. It creates basic paradigms that determine possibility and conditions for human activity in the world, and it is around cultural constants that the whole structure of being is built in the human consciousness. It is due to cultural constants, that a person obtains such “image of the surrounding medium” where all elements of the universe are structured and related with the person himself, and only within which a person may act. That means that only thanks to cultural constants “intentional personality” and “intentional world” are formed.

Just like “a set creates a psychological base for adopting a person to the surrounding medium and for transforming it according to his needs” (Nadirashvili 1978: 14), cultural constants establish the target and the method of the subconscious culture-determined adaptation of the world to the personal needs, as well as the adaptation of the person to the world.

A cultural constant complex includes such dynamic paradigms that reflect perception and set for action determined by this perception at the same time. At first glance, they may be operationally defined as some sorts of “images”: images of a source of good and a source of evil, a protecting and an opposing power, a we-image (an image of a group of people able to act), image of a field of action, condition of action, source of action, method of action and other possible images associated action of a person in the world. Besides the properties of such images, their disposition, ways of interconnection and interaction between them are of paramount relevant.

Thus, a cultural constant complex happens to be a system of images that describes the arena of action of a person as a member of the group that is the primary “we” for him (let us remind the reader that Shweder speaks of a so-called “intentional action” (Shweder 1991: 101)). And if so, there appears a base for the reaction of “external” (intentional) conflicts in a “dramatized” way, through the interaction of images, specific and peculiar for every culture (we do not yet speak of the internal conflicts determined through the acceptance of being as intentional reality by a person as an “intentional personality”; we only speak of the conflicts within the framework of the intentional world itself). Every image has its own “character” and certain relations with other images. Through them, every culture obtains a “canon of reality perception”, which is a complex of cultural representations. From this point of view, human activity is presented as an interaction of images, within which a person develops his behaviour, as though becoming one of the components of this perpetually moving system. And in this very context, which, actually, is culture, his fixed sets are developed.

***

Let us explain the functioning of cultural constants on a relatively simple example. Let’s say, that according to the rules of some story genre, some characters are supposed to be there: a villain, a knight, a lady etc. In each and every story these characters have names and individual features, but some common properties and models of relationships between them, dynamics of the plot required by the story genre remain the same. Generally, culture creates a similar canon for universe perception. It establishes such paradigms of perception that all objects or features of the external world are either matched to the “images” developed by culture, subject to more or less significant distortions, or are not at all perceived by a person within the given culture.

As environment of a sociocultural system changes, the cultural, political, economic conditions the people lives in also change. It means, that the experience the people is expected to perceive and its structure also changes. It is like a new play written under the same canon, but based on a new plot. The “pictures of the world” will change, but thanks to “cultural constants” their underlying structure will remain the same. One “intentional world” will replace another, but their fundament will still remain the same, based on the same “cultural constants” in the same dispositions; the “skeleton” of culture will remain, but the “meat” on the “skeleton” will be different.

“The New Guinea tribes-man whose inkblot responses were our starting point may in a decade have gone from his tribe’s traditional model of the cosmos <…> through a series of radical shifts. A Fundamental missionary may have persuaded him that in the Book of Genesis and what follows lies the source of the white man’s power. Within five more years he is voting for a representative in the House of Assembly, is co-owner of a truck, and has heard about men’s landing on a moon he perceived as a totemic deity ten years back. It is a mystery how a man can cope with such chaotic shifts of consciousness and remain same?” asked (maybe the basic question of anthropology) anthropologists R. and F. Keesings (Keesing, Keesing 1971: 357). Maybe the reason why the man remains sane is that such shifts may be not chaotic at all. Their main concern are the things the things that are not related to the frame of the current culture. The “skeleton” of the “New Guinea tribes-man” remained the same; the only components that changed were those, the mobility of which was allowed by his culture. And it makes no difference if for an external observer the changes seem global: every culture has its logic.

“Cultural constants” are not the contents of “images”; they are general “formal”, “technical” characteristics ascribed to them, which finally determine the order of manifestation and perception of all the images involved in the plot. Certain filling of the paradigms may vary, and that is when new modifications and “images of the world”, as well as all other images, occur. But in any case their filling will maintain the general attribute of all the images, their disposition, vision of the action modus the same and unchanged. These are the constants the cultural tradition in different modifications is crystallized around.

***

“Сultural constants” are not realized by a culture representative. They are tools for structuring and “rationalization” of the experience obtained from the external world. Though the “world view” formed in people’s consciousness on the basis of cultural constants may be criticized, cultural constants themselves are not subject to the people’s judgments at least because people do not see or aware of them. This is where the protective mechanisms of the human psyche play their part. Thanks to them, cultural constants never reveal their contents immediately in the consciousness of their bearers; they pop up only as ideas of some certain problems or objects, i.e. in the maximally specific shape. Going through the protective barrier of human psyche, cultural constants are, in a way, fractionized: they enter the consciousness zone not as a universal rule, common for a number of various phenomena, but as a vision of the most convenient action for the specific moment. Moreover, the ways of manifestation of cultural constants may be so diverse and multiple that sometimes it is really difficult to find a common tendency underneath.

The diversity of the ways for cultural constants to reveal themselves provides their “invisibility” and “invincibility”. In the event of an evident contradiction in the manifestation of cultural constants or a critical mismatch of the constants with the reality, it is not the cultural constant that is threatened, but a certain form of its manifestation. Some behaviour pattern may be rejected by an individual or a community as inconsistent, but the subconscious basis of this pattern will remain unchanged and find, in this way or another, its manifestation in some other forms. Therefore, in the periods of modification of the cultural consciousness, cultural constants just change their “costumes”.

***

The filling of cultural constants with some certain contents is a way of joining subconscious images with real phenomena (but not always within a specific tradition), or, speaking in psychoanalytic terms, is a transfer, or transposition of a unconscious complex to a real object. Such joining may be more or less stable and remain as long as an object can bear such a load within the culture-determined “picture of the world” and culture-determined experience of people, until it does not diverge from reality too much. Then another transfer occurs, but it is a transfer to a different оbject already. It is the intentional world transformation law. This is how, for example, the development or replacement of the “image of the protector” and “image of an enemy” (personified or not) occur.

Another similar phenomenon is what we may refer to as autotransfer: a person ascribes some properties typical of the unconscious “selfimage”, “we-image” (concept of “we” and concept of “I”) to himself. Therefore, a person is creating himself as an intentional personality, inscribing himself into the intentional community and the intentional world. The structure of relationship between unconscious images is transferred onto real experience, determining the ways of people’s actions (intentional action). People act in compliance with the properties they transfer onto themselves, within the framework of the vision of the community, its properties and relations lying in their unconscious. Therefore, “material flow” is used to extract some new elements that previously remained unnoticed an ignored; they become “meaning systems”, while others that formerly constituted the “meaning systems” will either retain their status as history and archaeology, or be thrown away, flushed back into “material flow”.

The object the transfer is made on becomes the key of the current version of the cultural tradition. All meaning connections of the ”world view” are concentrated around such “relevant objects”; they also set the plot in the life of society (sociocultural system), as they act as mediators for projecting the conflict between the “image of the source of good” and the “image of the source of evil” the culture assumes or allows, onto actual reality.

***

As new “meaning systems” become such and are then adopted, interiorized by a person dynamically, i.e. as a culture-determined script unfolds, we may suppose that cultural constants underlie the scripts admitted by the current culture as desired or acceptable, and, moreover, they serve as a base for building such scripts. In order to build such dynamic constructs as cultural scripts on the basis of cultural constants, it is necessary for the cultural constants themselves, acting as culture-determined mental images forming the basis for the culture as it is refracted in the psyche of its carrier, to be involved in dynamic interaction with each other. Culture is a “field of action”, as defined by Ernst Boesch (as we have mentioned above) not only because all of its elements interact with each other, but also because the frame the WHOLE culture is built on is dynamic in its core. This is the only fact we may use to explain how changes in one elements of the cultural system may lead to changes in its other elements without breaking the culture as a whole.

It is easier to understand as follows: cultural constants contain some models of actions that are the sets for some certain activity and the idea of the way of activity, the totality of which constitutes a prototype of a script that finds its reflection in any script brought to life.

In culture, any set provokes a counterset, thereby creating a frame of sets, on which “meaning systems” are “woven” and fixed, turning from “material flow” components into artefacts. It happens in the process of actualization of various specific cultural event scripts. New sets do not appear spontaneously; their target and intention is determined by culture as a whole. The frame for matching all possible specific scripts to be actualized in this or that culture is an idea of interactions underlying the culture, or, to be more precise, an idea of a principally possible structure of interactions acceptable in the given culture (considering all alternatives accepted by the culture). This idea is projected on every bearer of the given culture as an individual, acting within the culture. Intentionality, let it be general universal (“intentional world”) or an individual (“intentional personality”) one, reflects the idea of an action, an action of an “intentional personality” in the “intentional world”. Actions, activity of a personality in the world are the contents of the “intentionality” category not as much in the aspect of its objects, but in the aspect of its formal characteristics, and, therefore, of its models. The models are united into integrities of models, which are scripts, and scripts are generalized into the basic structure of a culture that we may refer to as unconscious internalized (implicit) general cultural script. Though it is not the “intentional world” itself yet, it is the frame, its “intentional scheme”.

Being an intentional scheme, general cultural script is specific for every culture, it lies beyond culture and bears a conflict in itself. Its extralogic nature is partially explained by its function to psychologically adapt the external reality, to make it more comfortable for people even if by distorting its perception (i.e. a general cultural script itself turns a person into an intentional personality within his culture) and a peculiar “rationalization”, for example, by psychological localization of all the evil of the world in one source, so that it does not seem to be spread all around the world. Being extralogical, or, to be more precise, intentionally logical, intentionally rationally perceivable, reality inevitably becomes fundamentally contradictory in the human consciousness, evoking certain sets for action to smoothen the contradictions. That is what motivate a person into action, i.e. directs him to actualize the old cultural scripts or to “spontaneously synthesize” some new ones on the basis of an existing script frame. Therefore, being intentionally perceived, objective reality becomes a projection of a general cultural script. That is how a cognitive artefact gains its motivation power, forcing a person to act in order to minimize the perceived contradictions, stimulates development of a set as an unconscious need for an appropriate cognition of activity.

Adoption of a culture by a child, or enculturation, means adoption of the script “intentionality”. Transmission of culture from one generation to another is carried out as a human being digests a huge amount of cultural event scripts and has the main principles of interaction, typical for the given culture, condensed in his consciousness and, what is especially important, in the unconscious. That is how a person unconsciously adopts, unconsciously generalizes cultural properties, cultural models determining the interaction patterns, and thereby perceives the implicit general cultural script specific for his culture. It should be noted that interaction principles can be common on different levels and in various aspects.

The implicit general cultural script may be correlated to the cultural constants complex, i.e. with the general scheme of perception-interaction in the world typical of the given culture. The cultural constants complex includes the vision of the ”right”, “correct”, and, partially, appropriate interaction (unlike the cultural script that creates the whole spectrum of interactions possible in the given culture). A general cultural script and cultural constants complex are two sides of the same medal, and both of them may be presented, on one hand, as a prism the culture bearer is looking at the world, and on another hand, as a totality of culture-determined models of action.

Cultural constants complex is a perceptive-activity scheme, and general cultural script is a projection of this scheme on the “intentional personalities” acting in the intentional world. Cultural constants complex may be to some extent defined as an idealized vision of the condition of the world making this or that action convenient, adapted to the human being, while implicit general cultural script is principally implicit. Moreover, if cultural constants may be sometimes decomposed into several elements, it is very complicated to do with a general cultural script. If cultural constants provide a sort of schematization of the general cultural script, its modal basis, then a general cultural script, being wider than this projection-scheme itself, includes all variations of actualizing cultural constants, acceptable and possible in the given culture. A general cultural script is a sophisticated cultural complex which includes clusters for ALL possibilities of perception and action represented in the given culture. A general cultural script is a skeleton of culture with a spine consisting of modal possibilities, modal structures of perception and action and branches of all the opportunities thinkable in the current culture, potentially including all variants of actions acceptable by the culture.

***

A general cultural script determined six types of artefacts listed above: (1) material artefacts (because they become meaningful only in the context of a “general cultural script”); (2) ideal artefacts (because they get inscribed in the models of action and become culturally meaningful through the general cultural script); (3) cognitive artefact (perception, representation or a scheme of an object associated with a set and, through the set, with a model of action in the consciousness and subconscious of an individual); (4) models of actions with the artefacts acting as a base for building specific and, inter alia, event cultural scripts; (5) objectives and values (as the ones determining the perception of reality and the direction of a set to an action); (6) intentional worlds (the only ones where intentional personalities may act). Now let us also add (7) cultural space of an action, including cultural constants as “technological images”. Let us remind the reader that artefacts (3), (4), and (5) are categorized as schemes. Now we may also specify that all the schemes correlated the intentional worlds with the cultural space of action. As schemes, cultural constants determine the modality of a general cultural script.

***

The cultural constants concept helps developing such an idea popular in psychological anthropology, as “distributing model of culture” that was promoted, particularly, by Theodor Schwartz (Schwartz 1994; Schwartz 1989; Schwartz 1978).

Similarly, in our “general cultural script concept” distribution of culture between its carrier also takes place; on the basis of the “cultural constants” the totality of “pictures of world” different from each other, for example, on the basis of various values, is formed.

It is important that “cultural constants” themselves do not contain any vision of the intention of the action and its moral evaluation. The intention and objective of the action may be set by “value configuration”. Cultural constants and value configuration are correlated as a way of action and an objective of action.

Further, the picture of the world (intentional world) may be regarded as derivative from cultural constants on one hand, and from the value orientation on the other. The existence of different value orientations, specific for different sociocultural system members and their socio-functional groups, inevitably leads to the fact that a sociocultural system does not have a single picture of the world (not a single intentional world), but a complex of intentional worlds interconnected with each other (having one and the same frame, which is the cultural constants system).

There is another component connected to the picture of the world, which is the cultural theme, the central theme for a given society. It would be correct to regard the “cultural theme” (ethos, culture pattern) (Benedict 1934: 36-37) as a type of a stable transfer which reflects the paradigm of “activity condition” in a culture bearers’ psychology. Being a result of a stable (which does not mean indestructible) transfer, a cultural system is included into the world view of various intracultural groups, and, therefore, into various value systems, and can manifest itself in diverse, or even mutually opposite interpretations. This or that perception of the “central cultural theme” depends on the value orientations of the sociocultural system members and their social-functional groups.

We may suggest that the distributing of culture (disintegration of the central cultural theme), based on the integral cultural constants, has a functional meaning. If a cultural constants system acts both as a model for the culture bearers’ action in the world, and as a model for their interaction with each other, then the distributing of culture is something like a trigger for a sociocultural system’s self-organization. Activity in the world and self-organization are two sides of the same medal. Through the dynamic perception of the surrounding world a cultural system structures both the “external” reality and itself as a component of such reality. If reality manifests itself to a human being as an arena, a field of action in a certain world view, then there is no surprise that it presents a system where it is possible to maintain balance and stability only if the system remains dynamic.

***

Cultural models of interaction are adaptation-activity models, regulating the character of sociocultural community members’ activity and interaction in the world, formed on the basis of a general cultural script appropriately refracted in certain situations. These models are the results of such refractions; they belong to different intracultural groups, interact with each other, so that in each of the groups the transfer objects are corrected in such a way that the intensiveness of the “image of the source of evil” decreases, and the images of “we” and the “protector” is enhanced. The interaction of different intracultural groups follows the cultural models of interaction as “role-playing” of these or those main aspects of the cultural theme. It is not always easy to see the common base in different situations. Quite often adaptation-activity models do not have any ideological substance; people follow them just because it is convenient for them to act this way, and only post-factum people substantiate their actions in any way.

If a world view as a derivative of the cultural constants’ complex is a principally dynamic system, it means that it initially contains a conflict perception of the world. Evidently, the conflict between the images of “we” and the “source of evil” is preset in it. And the perception of one’s native culture and society assumes some internal conflict, as the society structure is far from homogenous and it is not easily matched into the “we-image”. The existence of different pictures of the world based on common cultural constants, but different value systems, different interpretations of the basic cultural themes within one sociocultural system, leads to an inevitable conflict within a sociocultural system. And as the cultural constants system sets certain type of relationship between different components of the sociocultural system, it also sets the structure of the conflict itself, that acts as an “engine” that maintains the dynamism, essential for the survival of the given sociocultural system. It means that the intracultural conflict is functional. Every intracultural group acts by itself within its intentional world, and it is like a drama that unfolds act by act, where every action seems isolated and independent of the whole structure, but all of them still lead to creation of new social institutions, providing the sociocultural system as a whole with the opportunity of constructive activity. As in a picture of the world reality is always schematic, i.e., distorted, from outside the actions of the people may seem “not straightforward”, illogical. A human action, as it becomes a cultural phenomenon (artefact) and matches into the general structure of being, may be completely understood and rationally explained only within the logical framework of the given culture.

The topic of adaptive origin and the adaptive function of the interiorized general cultural script is worth separate mentioning. One of the central messages of psychological anthropology is the statement of an underlying connection between the immediate medium where a human being exists and the fundamental distinctive categories of his mind (Spiro 1984). The medium surrounding a human being is full of devices and tools (adaptations) of behaviour used by the previous generations in an embodied and (to a great degree) external form, remarked Michael Cole (Cole 1995:7). Famous culture expert Edward Markarian explained understanding of culture as a specific way of human activity, a way of human existence of adaptive nature. Ethnic cultures are historically developed ways of activity that have been ensuring the adaptation of various peoples to the conditions of the surrounding natural and social environment (Markarian 1978: 8-9). But what prevents us from stating that the medium surrounding a human being is full of “devices and tools (adaptations) of behaviour” having also a psychological and an ideal form, together with the “sets”? That is, first of all, the “function of culture as a specific means of human adaptation” (Markarian 1998: 84).

Let’s draw some conclusions.

We understand culture as a complex of meaning systems of different degrees of complexity, both conscious and unconscious. By meaning systems we understand a totality of mental components of artefacts of all levels, where the core is composed by a general cultural script, as only in a connection with it different objects and actions become meaningful in culture: from cognitive schemes of different things to event scripts, from material culture objects to their algorithms of operation, from simple instructions to the complicated self-organization mechanisms of the given culture bearers’ population (sociocultural systems), from intentional worlds to intentional personalities.

The core of culture (“the central zone” of culture) is manifested in the “general cultural script”, a projection of “cultural constants”, that determine the action conditions and interaction character for the persons and intraethnic groups involved in bringing it to life. The distribution of cultural roles or the distribution of culture happens in accordance with the general cultural script. This script determines the character of reality perception and the mechanisms for modifications and transformations of the whole sociocultural system which functions according to the script. Culture is a principally dynamic system. In the most general cultural script there is a functional conflict that allows a sociocultural system to preserve itself and maintain itself only in a dynamic balance, i.e. to remain in a continuous functionalconflict communication and interaction of the intracultural groups, thereby supporting the mechanisms of adaptation and transformation in the “operative” condition all the time.

A sociocultural system is a totality of bearers of this or that culture, united, first of all, by a general cultural script, allowing them to maintain the necessary level of communication and interaction in any situation. The presence of a functional intracultural conflict and its flawless operation proves a normal, active state of a sociocultural group (as it is the only condition when a culture performs all of its functions appropriately), and the circle of people able to take part in the actualization of the functional intracultural conflict, being the megascript of the given culture, draws the boundaries of such sociocultural community. In the end, this is the kind of participation that proves that a person belongs to the culture and acts in accordance with the implicit general cultural script set by it.

For the future development of culture studies it is required to shift from the totality of anthropological disciplines, such as psychological and cognitive anthropologies, to psychological culture studies, that would not only explain the culture-determined vision of the world and its influence on human activity (or, on the opposite, the influence of activity on the vision of the world), the correlation between mental meanings and external reality, distribution of culture and its adaptive, motivational, communicative, distributive functions, but also on the basis of culture-determined understanding of human psyche explain the functioning of society as a sociocultural system, mobile, alive, continuously changing, able to overcome crises and restructure itself in accordance with the current conditions and necessities.

The complex of anthropological sciences in the psychological culture studies part needs to be completed with Christian anthropology that would reveal not the illusory, but the true opportunities of human freedom, freedom of will, in this world that seems to be utterly determined by adaptations and culture, or in the world after the fall from grace.

References

Boesch, E. (1991). Symbolic Action Theory and Cultural Psychology. Berlin, Heidelberg, NY, L., Paris, Tokyo, Hongkong, Barselona, Budapest: Springel-Verlag.

Benedict R. (1934). Patterns of Culture. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Cole, M. (2003). Culture and Cognitive Science. Talk Presented to the Cognitive Science Program, U.C. Santa Barbara. Available at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/278406542_Culture_and_ Cognitive_Science (accessed on 22 September 2015).

Cole, M. (1996). Kul’turno-istoricheskaia pskihologiia [Cultural and historical psychology]. Moscow, Kogito-centr.

Cole, M. (1995). Kul’turnye mekhanizmy razvitiia [Cultural mechanisms of development], In Voprosy psikhologii [Psychology issues], 3.

D’Andrade, R. (1994). Cognitive Anthropology, In Schwartz Th., White G., Lutz С. (eds.) New direction in Psychological Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Andrade R. (1994). Shemas and Motivation, In D’Andrade R., Strauss C. (eds). Human Motive and Culture Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

D’Andrade, R. (1984). Cultural Meaning Systems, In Shweder R., LeVine R. (eds.) Cultural Theory. Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. Cambridge, L., NY., New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press.

Inkeles, A., Levinson, D. (1969). National Character: The study of Modal Personality and Sociocultural Systems, In Lindzey C. and Aronson E. (eds.). The Handbook of Social Psychology. Vol. IV. Massachusetts (Calif.), London, Ontario: Addison-Wesley.

Keesing P., Keesing F. (1971). New Perspectivers in Cultural Anthropology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Markarian, E. (1998). Capacity for World Strategic Management. Yerevan: Gitutun.

Markarian E. (1978). Ob iskhodnykh metodologicheskikh predposylkakh issledovaniia etnicheskikh kul’tur [On primary methodological prerequisites of ethnic cultures’ research], In Metodologicheskie problemy etnicheskikh kul’tur. [Methodological problems of ethnic cultures]. Erevan, izd-vo AN Arm.SSR.

Miller, J. (1993). Theory of Developmental Psychology. NY: Freeman.

Nadirashvili, Sh. (1978). Psikhologiia propagandy [Propaganda psychology]. Tbilisi: “Mecniereba”.

Nelson, K. (1981). Cognition in a Script Frammework, In Flavell J. and Ross L. (eds.) Social Cognitive Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norman, D. (1975). Explorations in cognition. San Francisco: Freeman.

Prangishvili, A. (1985). Ustanovka kak neosiazaemaia osnova psikhicheskogo otrazheniia [Set as an intangible base of psychical reflection], In Prangishvili A.S., Sherozija A.E., Bassina F.V. (eds.) Bessoznatel’noe. Priroda, funktsii, metody issledovaniia [The unconscious. Nature, functions, methods of research]. Tbilisi: “Mecniereba”, 4.

Schwartz, Th. (1994). Anthropology and Psychology, In Schwartz Th., White G., Lutz С. (eds.) New direction in Psychological Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schwartz Th. (1989). The Structure of National Cultures, In Funke P. (ed.) Understanding Of USA: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Tubengen: Gunter Narr Verlal.

Schwartz Th. (1978). Where is the culture? In Spindler G (ed.) The Making of Psycholodgical Anthropology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shweder, R. (1991). Thinking Through Cultures. Cambridge (Mass.), London (England): Harvard University Press.

Simon, H. (1981). Sciences of the artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Spiro M. (1984). Some reflections on Cultural determinism and relativism with Special Reference to Emotion and Reason, In Shweder R., LeVine R. (eds.) Cultural Theory. Essays on Mind, Self, and Emotion. Cambridge, L., NY., New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press.

Uznadze, D. (1961). Eksperimental’nye osnovy psikhologicheskoy ustanovki [Experimental basis of psychological set]. Tbilisi: Izdatel’stvo AN GrSSR.

Wartofsky, M. (1979). Models Representation And The Scientific Understanding. Dordrecht: Holland / Boston: USA / L.: England: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Культура как поле человеческого действия (опыт построения психокультурологической теории)

С.В. Лурье

Социологический институт РАН Россия, 190005, Санкт-Петербург, ул. 7-я Красноармейская, 25/14

В статье рассматривается гипотеза об обобщенном культурном сценарии, который пронизывает все аспекты жизни человека и общества. Обобщенный культурный сценарий специфичен для каждой культуры и формируется в сознании человека в процессе социализации и энкультурации. Это осуществляется, когда осваиваемые им частные событийные культурные сценарии конденсируются в его сознании и обобщаются. Рассматривается культурный контекст функционирования обобщенного культурного сценария – социокультурная система, состоящая из разных типов артефактов и в целом представляющая интенциональную систему. Сам обобщенный культурный сценарий рассматривается как интенциональная, артефактная система, превращающая человека в интенциональную личность. Ставится проблема о соотношении интенциональности человеческого мира и свободы воли.

Ключевые слова: обобщенный культурный сценарий, социокультурная система, культурные константы, интенциональный мир, интенциональная личность, установка, артефакт, когниция, энкультурациия, свобода воли.

Научная специальность: 22.00.00 – социологические науки, 24.00.00 – культурология